Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

| Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific War, World War II | |||||||

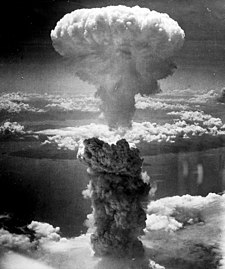

Atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima (left) and Nagasaki (right) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Manhattan District 509th Composite Group |

Second General Army | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | 90,000–166,000 killed in Hiroshima[1] 60,000–80,000 killed in Nagasaki[1] Total: 150,000–246,000+ killed |

||||||

The atomic bombings of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan were conducted by the United States during the final stages of World War II in 1945. The two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.

Following a firebombing campaign that destroyed many Japanese cities, the Allies prepared for a costly invasion of Japan. The war in Europe ended when Nazi Germany signed its instrument of surrender on 8 May, but the Pacific War continued. Together with the United Kingdom and the Republic of China, the United States called for a surrender of Japan in the Potsdam Declaration on 26 July 1945, threatening Japan with "prompt and utter destruction". The Japanese government ignored this ultimatum. American airmen dropped Little Boy on the city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, followed by Fat Man over Nagasaki on 9 August.

Within the first two to four months of the bombings, the acute effects killed 90,000–166,000 people in Hiroshima and 60,000–80,000 in Nagasaki, with roughly half of the deaths in each city occurring on the first day. The Hiroshima prefecture health department estimated that, of the people who died on the day of the explosion, 60% died from flash or flame burns, 30% from falling debris and 10% from other causes. During the following months, large numbers died from the effect of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, compounded by illness. In a US estimate of the total immediate and short term cause of death, 15–20% died from radiation sickness, 20–30% from burns, and 50–60% from other injuries, compounded by illness. In both cities, most of the dead were civilians, although Hiroshima had a sizeable garrison.

On 15 August, six days after the bombing of Nagasaki, Japan announced its surrender to the Allies, signing the Instrument of Surrender on 2 September, officially ending World War II. The bombings led, in part, to post-war Japan's adopting Three Non-Nuclear Principles, forbidding the nation from nuclear armament. The bombings' role in Japan's surrender and their ethical justification are still debated.

Contents

- 1 Background

- 2 Preparations

- 3 Hiroshima

- 4 Events of 7–9 August

- 5 Nagasaki

- 6 Plans for more atomic attacks on Japan

- 7 Surrender of Japan and subsequent occupation

- 8 Depiction, public response and censorship

- 9 Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission

- 10 Hibakusha

- 11 Debate over bombings

- 12 Notes

- 13 References

- 14 Further reading

- 15 External links

Background

Pacific War

In 1945, the Pacific War between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II had entered its fourth year. World War II was not winding down. Instead, the fighting was being prosecuted with ever-increasing fury. Of the 1.25 million battle casualties incurred by the United States in World War II, including both soldiers killed in action and wounded in action, nearly one million occurred in the twelve-month period from June 1944 to June 1945. December 1944 saw American battle casualties hit an all-time monthly high of 88,000 as a result of the German Ardennes Offensive.[2]

In the Pacific during this period, the Allies captured the Mariana and Palau Islands,[3] returned to the Philippines,[4] and invaded Borneo.[5] The policy of bypassing Japanese forces was abandoned. In order to free troops for use elsewhere, offensives were undertaken to reduce the Japanese forces remaining in Bougainville, New Guinea and the Philippines.[6] In April 1945, American forces landed on Okinawa, where heavy fighting continued until June. Along the way, the ratio of Japanese to American casualties dropped from 5 to 1 in the Philippines to 2 to 1 on Okinawa.[2]

Preparations to invade Japan

Plans were underway for the largest operation of the Pacific War, Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan, before the surrender of Nazi Germany on 8 May 1945.[7] The operation had two parts: Operations Olympic and Coronet. Set to begin in October 1945, Olympic involved a series of landings by the US Sixth Army intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island, Kyūshū.[8] Operation Olympic was to be followed in March 1946 by Operation Coronet, the capture of the Kantō Plain, near Tokyo on the Japanese island of Honshū by the US First, Eighth and Tenth Armies. The target date was chosen to allow for Olympic to complete its objectives, troops to be redeployed from Europe, and the Japanese winter to pass.[9]

Japan's geography made this invasion plan obvious to the Japanese as well; they were able to predict the Allied invasion plans accurately and thus adjust their defensive plan, Operation Ketsugō, accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyūshū, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations.[10] Four veteran divisions were withdrawn from the Kwantung Army in Manchuria in March 1945 to strengthen the forces in Japan,[11] and 45 new divisions were activated between February and May 1945. Most were immobile formations for coastal defense, but 16 were high quality mobile divisions.[12] In all, there were 2.3 million Japanese Army troops prepared to defend the Japanese home islands, another 4 million Army and Navy employees, and a civilian militia of 28 million men and women. Casualty predictions varied widely, but were extremely high. The Vice Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff, Vice Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi, predicted up to 20 million Japanese deaths.[13]

A study from 15 June 1945 by the Joint War Plans Committee,[14] who provided planning information to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, estimated that Olympic would result in between 130,000 and 220,000 US-casualties of which U.S. dead would be the range from 25,000 to 46,000. Delivered on 15 June 1945 after insight gained from the Battle of Okinawa, the study noted Japan's inadequate defenses due to the very effective sea blockade and the American firebombing campaign. The Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General of the Army George Marshall and General of the Army Douglas MacArthur signed documents agreeing with the Joint War Plans Committee estimate.[15]

The Americans were alarmed by the Japanese build up, which was accurately tracked through Ultra intelligence.[16] United States Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson was sufficiently concerned about high American estimates of probable casualties to commission his own study by Quincy Wright and William Shockley. Wright and Shockley spoke with Colonels James McCormack and Dean Rusk, and examined casualty forecasts by Michael E. DeBakey and Gilbert Beebe. Wright and Shockley estimated the invading Allies would suffer between 1.7 and 4 million casualties in such a scenario, of whom between 400,000 and 800,000 would be dead, while Japanese casualties would have been around 5 to 10 million.[17][18]

Marshall began contemplating the use of a weapon which was "readily available and which assuredly can decrease the cost in American lives":[19] poison gas. Quantities of phosgene, mustard gas, tear gas and cyanogen chloride were moved to Luzon from stockpiles in Australia and New Guinea in preparation for Operation Olympic, and General of the Army Douglas MacArthur ensured that Chemical Warfare Service units were trained in their use.[19]

Air raids on Japan

While the United States had developed plans for an air campaign against Japan prior to the Pacific War, the capture of Allied bases in the western Pacific in the first weeks of the conflict meant that this offensive did not begin until mid-1944 when the long-ranged Boeing B-29 Superfortress became ready for use in combat. Operation Matterhorn involved India-based B-29s staging through bases around Chengdu in China to make a series of raids on strategic targets in Japan between June 1944 and January 1945. However, it had failed to achieve the strategic objectives that the planners had intended for, largely because of logistical problems, the bomber's mechanical difficulties, the vulnerability of Chinese staging bases (see Operation Ichi-Go), and the extreme range required to reach key Japanese cities.

USAAF Brigadier General Haywood S. Hansell determined that Guam, Tinian and Saipan in the Mariana Islands would better serve as B-29 bases, but they were in Japanese hands. Strategies were shifted to accommodate the air war, and the islands were captured between June and August 1944. Air bases were developed, and B-29 operations commenced from the Marianas in November 1944, greatly expanding the scope of the strategic bombing campaign against Japan.[23] More importantly, these bases were safe from Japanese attacks and easily resupplied by cargo ships. The XXI Bomber Command, commanded by Haywood S. Hansell, began missions against Japan in October 1944. The early attempts to bomb Japan from the Marianas proved just as ineffective as the China based B-29s had been. Hansell continued the practice of conducting so-called high-altitude precision bombing even after these tactics had not produced acceptable results. These efforts proved unsuccessful due to logistical difficulties with the remote location, technical problems with the new and advanced aircraft, unfavorable weather conditions, and ultimately enemy action.[23] Hansell had "poor intelligence about Japanese industry and lacked maps."

Hansell's successor, General Curtis LeMay assumed command in January 1945 and continued to use the same tactics, with equally unsatisfactory results. LeMay realized that he would have to change tactics and decided that low-level incendiary raids against Japanese cities was only way to destroy their production capabilities, shifting from precision bombing to area and saturation bombing as the British RAF had conducted in Germany (see Area bombing directive) in the European Theatre before.[24] The attacks initially targeted key industrial facilities but from March 1945, they were frequently directed against urban areas mainly because Japanese authorities dispersed the industrial equipment and machinery throughout the nearby cities to limit the effects of the bombings. "The line between military and civilian, residential, and industrial was often non-existent."[24] Over the next six months, the XXI Bomber Command under LeMay firebombed 67 Japanese cities. The firebombing of Tokyo codenamed Operation Meetinghouse on 9–10 March killed an estimated 100,000 people and destroyed 16 square miles (41 km2) of the city with 267,000 buildings in a single night–the deadliest bombing raid of the war. The capture of Okinawa in June 1945 provided airfields even closer to the Japanese mainland, allowing the bombing campaign to be escalated further. Aircraft flying from Allied aircraft carriers and the Ryukyu Islands also regularly struck targets in Japan during 1945 in preparation for Operation Downfall.[25]

The Japanese military was unable to stop the Allied attacks and the country's civil defense preparations proved inadequate. From April 1945, the Japanese Army and Naval Air Forces stopped attempting to intercept the air raids in order to preserve fighter aircraft to counter the expected invasion.[26] By mid-1945 the Japanese also only occasionally scrambled aircraft to intercept individual B-29s conducting reconnaissance sorties over the country in order to conserve supplies of fuel.[27] By July 1945, the Japanese had stockpiled 1,156,000 US barrels (137,800,000 l; 36,400,000 US gal; 30,300,000 imp gal) of avgas for the invasion of Japan.[28]

Atomic bomb development

Working in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada, with their respective projects Tube Alloys and Chalk River Laboratories,[29][30] the Manhattan Project, under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, designed and built the first atomic bombs.[31] Preliminary research began in 1939, originally in fear that the Nazi atomic bomb project would develop atomic weapons first.[32] In May 1945, the defeat of Germany caused the focus to turn to use against Japan.[33]

Two types of bombs were eventually devised by scientists and technicians at Los Alamos under American physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. The Hiroshima bomb, known as Little Boy, was a gun-type fission weapon made with uranium-235, a rare isotope of uranium extracted in giant factories in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.[34] The other was an implosion-type nuclear weapon using plutonium-239, a synthetic element created in nuclear reactors at Hanford, Washington. A test implosion weapon, the gadget, was detonated at Trinity Site, on 16 July 1945, near Alamogordo, New Mexico.[35] The Nagasaki bomb, Fat Man was also an implosion device.[36]

Preparations

Organization and training

The 509th Composite Group was constituted on 9 December 1944, and activated on 17 December 1944, at Wendover Army Air Field, Utah, commanded by Colonel Paul Tibbets.[37] Tibbets was assigned to organize and command a combat group to develop the means of delivering an atomic weapon against targets in Germany and Japan. Because the flying squadrons of the group consisted of both bomber and transport aircraft, the group was designated as a "composite" rather than a "bombardment" unit.

Working with the Manhattan Project at Site Y in Los Alamos, New Mexico, Tibbets selected Wendover for his training base over Great Bend, Kansas, and Mountain Home, Idaho because of its remoteness.[38] On 10 September 1944, the 393rd Bomb Squadron, a B-29 Superfortress unit, arrived at Wendover from the 504th Bombardment Group (Very Heavy) at Fairmont Army Air Base, Nebraska, where it had been in group training since 12 March. When its parent group deployed to the Mariana Islands in early November 1944, the squadron was assigned directly to the Second Air Force until creation of the 509th Composite Group.[39] Originally consisting of twenty-one crews, fifteen were selected to continue training and were organized into three flights of five crews, lettered A, B, and C.

The 320th Troop Carrier Squadron (TCS), the other flying unit of the 509th, came into being because of the highly secret work of the group. The organization that was to become the 509th required its own transports for the movement of both personnel and materiel, resulting in creation of an ad hoc unit nicknamed "The Green Hornet Line".[39][40] Crews for this unit were acquired from the six 393rd crews not selected to continue B-29 training, some of whom chose to remain with the 509th rather than be assigned to a replacement pool of the Second Air Force. They began using Curtiss C-46 Commandos and C-47 Skytrains already at Wendover, and after November 1944 flew five acquired C-54 Skymasters.[41] The 320th TCS was formally activated at the same time as the group.[37]

Other support units were activated at Wendover from personnel already present and working with its Project W-47, which was later superseded by Project Alberta, or in the 216th Base Unit, both of which were affiliated with the Project Y. The 390th Air Service Group was created as the command echelon for the 603rd Air Engineering Squadron, the 1027th Air Material squadron, and its own Air Base Support Squadron, but as these units became independent operationally, acted as the basic support unit for the entire 509th Composite Group in providing quarters, rations, medical care, postal service and other basic support functions. The 603rd Air Engineering Squadron was unique in that it provided depot-level B-29 maintenance in the field, obviating the necessity of sending aircraft back to the United States for major repairs. The 603rd made a number of modifications to the first contract order of Silverplate B-29s that were later incorporated as specifications for the combat models.

The 393rd Bomb Squadron began replacement of its original B-29s with modified Silverplate aircraft with the delivery of three new B-29s in mid-October 1944.[40] These aircraft had extensive bomb bay modifications and a "weaponeer" station installed, but initial training operations identified numerous other modifications necessary to the mission, particularly in reducing the overall weight of the aircraft to offset the heavy loads it would be required to carry. Five more Silverplates were delivered in November and six in December, giving the group 14 for its training operations. In January and February 1945, 10 of the 15 crews under the command of the Group S-3 (operations officer) were assigned temporary duty at Batista Field, San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba, where they trained in long-range over-water navigation.[42]

On 6 March 1945, the 1st Ordnance Squadron (Special, Aviation) was activated at Wendover, again from Army Air Forces personnel on hand or already at Los Alamos, and concurrent with the activation of Project Alberta. Its purpose was to provide trained personnel and special equipment to the group to enable it to assemble atomic weapons at its operating base, thereby allowing the weapons to be transported more safely in their component parts. A rigorous candidate selection process was used to recruit personnel, with reportedly an 80% "washout" rate, and those made a part of the unit were not permitted transfer until the end of the war, nor were they allowed to travel without escorts from Military Intelligence units.[43]

With the addition of the 1st Ordnance Squadron to its roster, the 509th Composite Group had an authorized strength of 225 officers and 1,542 enlisted men, almost all of whom deployed to Tinian. The 320th Troop Carrier Squadron did not officially deploy but kept its base of operations at Wendover. In addition to its authorized strength, the 509th had attached to it on Tinian 51 civilian and military personnel of Project Alberta,[44] known as the 1st Technical Detachment.[45] There were two representatives from Washington, D.C., Brigadier General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, and Rear Admiral William R. Purnell of the Military Policy Committee.[46] They were on hand to decide higher policy matters on the spot. Along with Captain William S. Parsons, the commander of Project Alberta, they became known as the "Tinian Joint Chiefs".[47]

The 509th began replacement of its 14 training Silverplates in February 1945 by transferring four to the 216th Base Unit. In April they began receiving Silverplates of the third modification increment and the remaining ten training B-29s were placed in storage. Each bombardier completed at least 50 practice drops of inert pumpkin bombs and Tibbets declared his group combat-ready.[48] Preparation for Overseas Movement (POM) began in April.

Choice of targets

General of the Army George Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the Army, asked Groves to nominate specific targets for bombing, subject to approval by himself and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. Groves formed a Target Committee in April 1945 chaired by himself, that included his deputy, Brigadier General Thomas Farrell; one of his staff, Major John A. Derry; Colonel William P. Fisher, Joyce C. Stearns and David M. Dennison from the USAAF; and scientists John von Neumann, Robert R. Wilson and William C. Penney from the Manhattan Project. The Target Committee met on 27 April; at Los Alamos on 10 May, where it was able to talk to the scientists and technicians there; and finally in Washington on 28 May, where it was briefed by Colonel Paul Tibbets and Commander Frederick Ashworth, and the Manhattan Project's scientific advisor, Richard C. Tolman.[49]

The Target Committee nominated four targets: Kokura, the site of one of Japan's largest munitions plants; Hiroshima, an embarkation port and industrial center that was the site of a major military headquarters; Niigata, a port with industrial facilities including steel and aluminium plants and an oil refinery; and Kyoto, a major industrial center. The target selection was subject to the following criteria:

- The target was larger than 3 mi (4.8 km) in diameter and was an important target in a large urban area.

- The blast would create effective damage.

- The target was unlikely to be attacked by August 1945. "Any small and strictly military objective should be located in a much larger area subject to blast damage in order to avoid undue risks of the weapon being lost due to bad placing of the bomb."[50]

These cities were largely untouched during the nightly bombing raids and the Army Air Force agreed to leave them off the target list so accurate assessment of the weapon could be made. Hiroshima was described as "an important army depot and port of embarkation in the middle of an urban industrial area. It is a good radar target and it is such a size that a large part of the city could be extensively damaged. There are adjacent hills which are likely to produce a focusing effect which would considerably increase the blast damage. Due to rivers it is not a good incendiary target."[50]

The goal of the weapon was to convince Japan to surrender unconditionally in accordance with the terms of the Potsdam Declaration. The Target Committee stated that "It was agreed that psychological factors in the target selection were of great importance. Two aspects of this are (1) obtaining the greatest psychological effect against Japan and (2) making the initial use sufficiently spectacular for the importance of the weapon to be internationally recognized when publicity on it is released. Kyoto had the advantage of being an important center for military industry, as well an intellectual center and hence better able to appreciate the significance of the weapon. The Emperor's palace in Tokyo has a greater fame than any other target but is of least strategic value."[50]

Edwin O. Reischauer, a Japan expert for the US Army Intelligence Service, was incorrectly said to have prevented the bombing of Kyoto.[50] In his autobiography, Reischauer specifically refuted this claim:

... the only person deserving credit for saving Kyoto from destruction is Henry L. Stimson, the Secretary of War at the time, who had known and admired Kyoto ever since his honeymoon there several decades earlier.[51]

On 25 July, Nagasaki was put on the target list in place of Kyoto.[52]

Leaflets

For several months, the US had dropped more than 63 million leaflets across Japan, warning civilians of air raids. Many Japanese cities suffered terrible damage from aerial bombings, some even 97% destruction. In general, the Japanese regarded the leaflet messages as truthful, however, anyone who was caught in possession of a leaflet was arrested by the Japanese government.[53] Leaflet texts were prepared by recent Japanese prisoners of war because they were thought to be the best choice "to appeal to their compatriots."[54]

In preparation for dropping an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, US military leaders had decided against a demonstration bomb, and they also decided against a special leaflet warning, in both cases because of the uncertainty of a successful detonation, and the wish to maximize psychological shock.[55] No warning was given to Hiroshima that a new and much more destructive bomb was going to be dropped.[56] Various history books give conflicting information about when the last leaflets were dropped on Hiroshima prior to the atomic bomb: Robert Jay Lifton writes that it was 27 July[56] and Theodore H. McNelly writes that it was 30 July[55] but the USAAF history notes 11 cities targeted with leaflets on 27 July, none being Hiroshima, and no leaflet sorties on 30 July.[57] Other leaflet sorties were undertaken on 1 and 4 August, according to the official USAAF chronology. It is very likely that Hiroshima was leafleted in late July or early August, as survivor accounts talk about a delivery of leaflets a few days before the atomic bomb was dropped.[56] One such leaflet lists 12 cities targeted for firebombing: Otaru, Akita, Hachinohe, Fukushima, Urawa, Takayama, Iwakuni, Tottori, Imabari, Yawata, Miyakonojo, and Saga. Hiroshima was not listed.[58][59][60][61]

Potsdam ultimatum

On 26 July, Allied leaders issued the Potsdam Declaration outlining terms of surrender for Japan. It was presented as an ultimatum and stated that without a surrender, the Allies would attack Japan, resulting in "the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland". The atomic bomb was not mentioned in the communiqué. On 28 July Japanese papers reported that the declaration had been rejected by the Japanese government. That afternoon, Prime Minister Suzuki Kantarō declared at a press conference that the Potsdam Declaration was no more than a rehash (yakinaoshi) of the Cairo Declaration and that the government intended to ignore it (mokusatsu, "kill by silence").[62] The statement was taken by both Japanese and foreign papers as a clear rejection of the declaration. Emperor Hirohito, who was waiting for a Soviet reply to non-committal Japanese peace feelers, made no move to change the government position.[63]

Under the 1943 Quebec Agreement with the United Kingdom, the United States had agreed that nuclear weapons would not be used against another country without mutual consent. In June 1945 the head of the British Joint Staff Mission, Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, agreed that the use of nuclear weapons against Japan would be officially recorded as a decision of the Combined Policy Committee.[64] At Potsdam, Truman agreed to a request from the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill, that Britain be represented when the atomic bomb was dropped. William Penney and Group Captain Leonard Cheshire were sent to Tinian, but found that Major General Curtis LeMay would not let them accompany the mission. All they could do was send a strongly worded signal back to Wilson.[65]

Hiroshima

Hiroshima during World War II

At the time of its bombing, Hiroshima was a city of both industrial and military significance. A number of military camps were located nearby, including the headquarters of Field Marshal Shunroku Hata's 2nd General Army which commanded the defense of all southern Japan.[66] Field Marshal Hata's 2nd General Army was headquartered in the Hiroshima Castle and his command consisted of some 400,000 men, most of whom were on Kyushu where an Allied invasion was correctly expected.[67] Also present in Hiroshima was the headquarters of the 5th Division, 59th Army, and most of the 224th Division, a recently formed mobile unit.[68] The city was defended by five batteries of 7-and-8-centimetre (2.8 and 3.1 in) anti-aircraft guns of the IJA 3rd AAA Division, including units from the 121st and 122nd AA Regiments and the 22nd and 45th Separate AA Battalions.[69] In total, over 40,000 military personnel were stationed in the city.[70]

Hiroshima was a minor supply and logistics base for the Japanese military but it also had large depots of military supplies and was a key center for shipping.[71] The city was a communications center, a storage point, and an assembly area for troops. It was one of several Japanese cities left deliberately untouched by American bombing, allowing a pristine environment to measure the damage caused by the atomic bomb.[72]

The center of the city contained several reinforced concrete buildings and lighter structures. Outside the center, the area was congested by a dense collection of small wooden workshops set among Japanese houses. A few larger industrial plants lay near the outskirts of the city. The houses were constructed of wood with tile roofs, and many of the industrial buildings were also built around wood frames. The city as a whole was highly susceptible to fire damage.[73]

The population of Hiroshima had reached a peak of over 381,000 earlier in the war, but prior to the atomic bombing the population had steadily decreased because of a systematic evacuation ordered by the Japanese government. At the time of the attack, the population was approximately 340,000–350,000.[1] Residents wondered why Hiroshima had been spared destruction by firebombing.[74] Some speculated that the city was to be saved for US occupation headquarters, others thought perhaps their relatives in Hawaii and California had petitioned the US government to avoid bombing Hiroshima.[75] More realistic city officials had ordered buildings torn down to create long, straight firebreaks, beginning in 1944.[76] Firebreaks continued to be expanded and extended, right up to the morning of 6 August 1945.[77]

The bombing

Hiroshima was the primary target of the first nuclear bombing mission on 6 August, with Kokura and Nagasaki as alternative targets. The 393d Bombardment Squadron B-29 Enola Gay, piloted by Tibbets, took off from North Field airbase on Tinian, about six hours flight time from Japan. The Enola Gay (named after Tibbets' mother) was accompanied by two other B-29s. The Great Artiste, commanded by Major Charles Sweeney, carried instrumentation, and a then-nameless aircraft later called Necessary Evil, commanded by Captain George Marquardt, served as the photography aircraft.[39]

| Aircraft | Pilot | Call Sign | Mission role |

| Straight Flush | Major Claude R. Eatherly | Dimples 85 | Weather reconnaissance (Hiroshima) |

| Jabit III | Major John A. Wilson | Dimples 71 | Weather reconnaissance (Kokura) |

| Full House | Major Ralph R. Taylor | Dimples 83 | Weather reconnaissance (Nagasaki) |

| Enola Gay | Colonel Paul W. Tibbets | Dimples 82 | Weapon Delivery |

| The Great Artiste | Major Charles W. Sweeney | Dimples 89 | Blast measurement instrumentation |

| Necessary Evil | Captain. George W. Marquardt | Dimples 91 | Strike observation and photography |

| Top Secret | Captain Charles F. McKnight | Dimples 72 | Strike spare—did not complete mission |

After leaving Tinian the aircraft made their way separately to Iwo Jima to rendezvous at 2,440 meters (8,010 ft) and set course for Japan. The aircraft arrived over the target in clear visibility at 9,855 meters (32,333 ft). Parsons, who was in command of the mission, armed the bomb during the flight to minimize the risks during takeoff. His assistant, Second Lieutenant Morris R. Jeppson, removed the safety devices 30 minutes before reaching the target area.[79]

About an hour before the bombing, Japanese early warning radar detected the approach of some American aircraft headed for the southern part of Japan. An alert was given and radio broadcasting stopped in many cities, among them Hiroshima. At nearly 08:00, the radar operator in Hiroshima determined that the number of planes coming in was very small—probably not more than three—and the air raid alert was lifted. To conserve fuel and aircraft, the Japanese had decided not to intercept small formations. Hiroshima's anti-aircraft batteries were put on alert, but held their fire; because anti-aircraft guns caused significant collateral damage and casualties on the ground, the anti-aircraft gunners of all belligerents in the war were typically ordered to avoid firing on small numbers of enemy aircraft, especially if they were stationed in or near large population centers.[citation needed]

The normal radio broadcast warning was given to the people that it might be advisable to go to air-raid shelters if B-29s were actually sighted. However a reconnaissance mission was assumed because at 07:31 the first B-29 to fly over Hiroshima at 32,000 feet (9,800 m) had been the weather observation aircraft Straight Flush that sent a Morse code message to the Enola Gay indicating that the weather was good over the primary target. Because it then turned out to sea, the 'all clear' was sounded in the city. At 08:09 Colonel Tibbets started his bomb run and handed control over to his bombardier.[80]

The release at 08:15 (Hiroshima time) went as planned, and the gravity bomb known as "Little Boy", a gun-type fission weapon with about 64 kg (140 lb) of uranium-235, took 43 seconds to fall from the aircraft flying at 31,060 feet (9,470 m) to the predetermined detonation height about 1,968 feet (600 m) above the city. The Enola Gay traveled 11.5 mi (18.5 km) before it felt the shock waves from the blast.[81]

Due to crosswind, it missed the aiming point, the Aioi Bridge, by approximately 800 ft (240 m) and detonated directly over Shima Surgical Clinic.[82] It created a blast equivalent to 16 kilotons of TNT (67 TJ).[83] (The U-235 weapon was considered very inefficient, with only 1.7% of its material fissioning.)[84] The radius of total destruction was about one mile (1.6 km), with resulting fires across 4.4 square miles (11 km2).[85] Americans estimated that 4.7 square miles (12 km2) of the city were destroyed. Japanese officials determined that 69% of Hiroshima's buildings were destroyed and another 6–7% damaged.[86]

Some 70,000–80,000 people, or some 30% of the population of Hiroshima, were killed by the blast and resultant firestorm,[87] and another 70,000 injured.[88] Over 90% of the doctors and 93% of the nurses in Hiroshima were killed or injured—most had been in the downtown area which received the greatest damage.[89] Out of some 70,000-80,000 people killed, 20,000 were soldiers.[90] Most elements of the Japanese 2nd General Army were at physical training on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle when the bomb exploded. Barely 900 yards from the explosion's hypocenter, the castle and its residents were vaporized. The bomb also killed 12 American airmen who were imprisoned at the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters located about 1,300 feet (400 meters) from the hypocenter of the blast.[91] All died in less than a second.[92]

Japanese realization of the bombing

The Tokyo control operator of the Broadcasting Corporation of Japan noticed that the Hiroshima station had gone off the air. He tried to re-establish his program by using another telephone line, but it too had failed.[93] About 20 minutes later the Tokyo railroad telegraph center realized that the main line telegraph had stopped working just north of Hiroshima. From some small railway stops within 16 km (9.9 mi) of the city came unofficial and confused reports of a terrible explosion in Hiroshima. All these reports were transmitted to the headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff.

Military bases repeatedly tried to call the Army Control Station in Hiroshima. The complete silence from that city puzzled the men at headquarters; they knew that no large enemy raid had occurred and that no sizable store of explosives was in Hiroshima at that time. A young officer of the Japanese General Staff was instructed to fly immediately to Hiroshima, to land, survey the damage, and return to Tokyo with reliable information for the staff. It was generally felt at headquarters that nothing serious had taken place and that the explosion was just a rumor.[94]

The staff officer went to the airport and took off for the southwest. After flying for about three hours, while still nearly 160 km (99 mi) from Hiroshima, he and his pilot saw a great cloud of smoke from the bomb. In the bright afternoon, the remains of Hiroshima were burning. Their plane soon reached the city, around which they circled in disbelief. A great scar on the land still burning and covered by a heavy cloud of smoke was all that was left. They landed south of the city, and the staff officer, after reporting to Tokyo, began to organize relief measures.[94]

By 8 August 1945, newspapers in the US were reporting that broadcasts from Radio Tokyo had described the destruction observed in Hiroshima. "Practically all living things, human and animal, were literally seared to death", Japanese radio announcers said in a broadcast received by Allied sources.[95]

Post-attack casualties

Around 1,900 cancer deaths can be attributed to the after-effects of the bombs. An epidemiology study by the Japanese Radiation Effects Research Foundation states that from 1950 to 2000, 46% of leukemia deaths and 11% of solid cancer deaths among the bomb survivors were due to radiation from the bombs, the statistical excess being estimated at 200 leukemia and 1700 solid cancers.[96]

Survival of some structures

Some of the reinforced concrete buildings in Hiroshima had been very strongly constructed because of the earthquake danger in Japan, and their framework did not collapse even though they were fairly close to the blast center. Eizo Nomura (野村 英三 Nomura Eizō) was the closest known survivor, who was in the basement of a reinforced concrete building (it remained as the Rest House after the war) only 170 m (560 ft) from ground zero (the hypocenter) at the time of the attack.[97][98] He lived into his 80s.[99][100][101] Akiko Takakura (高蔵 信子 Takakura Akiko) was among the closest survivors to the hypocenter of the blast. She had been in the solidly built Bank of Hiroshima only 300 meters (980 ft) from ground-zero at the time of the attack.[102] Since the bomb detonated in the air, the blast was directed more downward than sideways, which was largely responsible for the survival of the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, now commonly known as the Genbaku, or A-bomb Dome. This building was designed and built by the Czech architect Jan Letzel, and was only 150 m (490 ft) from ground zero. The ruin was named Hiroshima Peace Memorial and was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996 over the objections of the United States and China, which expressed reservations on the grounds that other Asian nations were the ones who suffered the greatest loss of life and property, and a focus on Japan lacked historical perspective.[103]

| Hiroshima bombing | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Events of 7–9 August

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

After the Hiroshima bombing, Truman issued a statement announcing the use of the new weapon. He stated, "We may be grateful to Providence" that the German atomic bomb project had failed, and that the United States and its allies had "spent two billion dollars on the greatest scientific gamble in history—and won." Truman then warned Japan:

If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.[104]

The Japanese government still did not react to the Potsdam Declaration. Emperor Hirohito, the government, and the war council were considering four conditions for surrender: the preservation of the kokutai (Imperial institution and national polity), assumption by the Imperial Headquarters of responsibility for disarmament and demobilization, no occupation of the Japanese Home Islands, Korea, or Formosa, and delegation of the punishment of war criminals to the Japanese government.[105]

The Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov had informed Tokyo of the Soviet Union's unilateral abrogation of the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact on 5 April. At two minutes past midnight on 9 August, Tokyo time, Soviet infantry, armor, and air forces had launched the Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation. Four hours later, word reached Tokyo of the Soviet Union's official declaration of war. The senior leadership of the Japanese Army began preparations to impose martial law on the nation, with the support of Minister of War Korechika Anami, in order to stop anyone attempting to make peace.

Nagasaki

I realize the tragic significance of the atomic bomb ... It is an awful responsibility which has come to us ... We thank God that it has come to us, instead of to our enemies; and we pray that He may guide us to use it in His ways and for His purposes.—President Harry S. Truman, August 9, 1945[106]

Nagasaki during World War II

The city of Nagasaki had been one of the largest sea ports in southern Japan and was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials. The four largest companies in the city were Mitsubishi Shipyards, Electrical Shipyards, Arms Plant, and Steel and Arms Works, which employed about 90% of the city's labor force, and accounted for 90% of the city's industry.

Nagasaki was not the target of large-scale bombing prior to 9 August 1945. However, the city had been previously bombed on a small scale five times. Of these raids,[107] on 1 August, a number of conventional high-explosive bombs were dropped on the city. A few hit in the shipyards and dock areas in the southwest portion of the city, several hit the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, and six bombs landed at the Nagasaki Medical School and Hospital, with three direct hits on buildings there. While the damage from these bombs was relatively small, it created considerable concern in Nagasaki and many people—principally school children—were evacuated to rural areas for safety, thus reducing the population in the city at the time of the nuclear attack. By early August, the city was defended by the IJA 134th AAA Regiment of the 4th AAA Division with four batteries of 7 cm (2.8 in) anti-aircraft guns and two searchlight batteries.[69]

In contrast to many modern aspects of Hiroshima, almost all of the buildings were of old-fashioned Japanese construction, consisting of wood or wood-frame buildings with wood walls (with or without plaster) and tile roofs. Many of the smaller industries and business establishments were also situated in buildings of wood or other materials not designed to withstand explosions. Nagasaki had been permitted to grow for many years without conforming to any definite city zoning plan; residences were erected adjacent to factory buildings and to each other almost as closely as possible throughout the entire industrial valley. On the day of the bombing, an estimated 263,000 were in Nagasaki, including 240,000 Japanese residents, 10,000 Korean residents, 2,500 conscripted Korean workers, 9,000 Japanese soldiers, 600 conscripted Chinese workers, and 400 prisoners of war.[108]

To the north of Nagasaki, there was a camp holding British Commonwealth prisoners of war, some of whom were working in the coal mines and only found out about the bombing when they came to the surface.[70]

The bombing

Responsibility for the timing of the second bombing was delegated to Tibbets. Scheduled for 11 August against Kokura, the raid was moved earlier by two days to avoid a five-day period of bad weather forecast to begin on 10 August.[109] Three bomb pre-assemblies had been transported to Tinian, labeled F-31, F-32, and F-33 on their exteriors. On 8 August, a dress rehearsal was conducted off Tinian by Sweeney using Bockscar as the drop airplane. Assembly F-33 was expended testing the components and F-31 was designated for the August 9 mission.[110]

| Aircraft | Pilot | Call Sign | Mission role |

| Enola Gay | Captain George W. Marquardt | Dimples 82 | Weather reconnaissance (Kokura) |

| Laggin' Dragon | Captain Charles F. McKnight | Dimples 95 | Weather reconnaissance (Nagasaki) |

| Bockscar | Major Charles W. Sweeney | Dimples 77 | Weapon Delivery |

| The Great Artiste | Captain Frederick C. Bock | Dimples 89 | Blast measurement instrumentation |

| Big Stink | Major James I. Hopkins, Jr. | Dimples 90 | Strike observation and photography |

| Full House | Major Ralph R. Taylor | Dimples 83 | Strike spare—did not complete mission |

On the morning of 9 August 1945, the B-29 Superfortress Bockscar, flown by Sweeney's crew, carried Fat Man, with Kokura as the primary target and Nagasaki the secondary target. The mission plan for the second attack was nearly identical to that of the Hiroshima mission, with two B-29s flying an hour ahead as weather scouts and two additional B-29s in Sweeney's flight for instrumentation and photographic support of the mission. Sweeney took off with his weapon already armed but with the electrical safety plugs still engaged.[112]

This time Penney and Cheshire were allowed to accompany the mission, flying as observers on the third plane, Big Stink, which was flown by the group's Operations Officer, Major James I. Hopkins, Jr. Observers aboard the weather planes reported both targets clear. When Sweeney's aircraft arrived at the assembly point for his flight off the coast of Japan, Big Stink failed to make the rendezvous. Bockscar and the instrumentation plane circled for 40 minutes without locating Hopkins. Already 30 minutes behind schedule, Sweeney decided to fly on without Hopkins.[112]

By the time they reached Kokura a half hour later, a 70% cloud cover had obscured the city, inhibiting the visual attack required by orders. After three runs over the city, and with fuel running low because a transfer pump on a reserve tank had failed before take-off, they headed for their secondary target, Nagasaki.[112] Fuel consumption calculations made en route indicated that Bockscar had insufficient fuel to reach Iwo Jima and would be forced to divert to Okinawa. After initially deciding that if Nagasaki were obscured on their arrival the crew would carry the bomb to Okinawa and dispose of it in the ocean if necessary, the weaponeer, Navy Commander Frederick Ashworth, decided that a radar approach would be used if the target was obscured.[113]

At about 07:50 Japanese time, an air raid alert was sounded in Nagasaki, but the "all clear" signal was given at 08:30. When only two B-29 Superfortresses were sighted at 10:53, the Japanese apparently assumed that the planes were only on reconnaissance and no further alarm was given.

A few minutes later at 11:00, The Great Artiste, the support B-29 flown by Captain Frederick C. Bock, dropped instruments attached to three parachutes. These instruments also contained an unsigned letter to Professor Ryokichi Sagane, a nuclear physicist at the University of Tokyo who studied with three of the scientists responsible for the atomic bomb at the University of California, Berkeley, urging him to tell the public about the danger involved with these weapons of mass destruction. The messages were found by military authorities but not turned over to Sagane until a month later.[114] In 1949, one of the authors of the letter, Luis Alvarez, met with Sagane and signed the document.[115]

At 11:01, a last minute break in the clouds over Nagasaki allowed Bockscar's bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, to visually sight the target as ordered. The Fat Man weapon, containing a core of about 6.4 kg (14 lb) of plutonium, was dropped over the city's industrial valley. It exploded 43 seconds later at 469 m (1,539 ft) above the ground halfway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works (Torpedo Works) in the north. This was nearly 3 km (1.9 mi) northwest of the planned hypocenter; the blast was confined to the Urakami Valley and a major portion of the city was protected by the intervening hills.[116] The resulting explosion had a blast yield equivalent to 21 kt (88 TJ).[117] The explosion generated heat estimated at 3,900 °C (7,050 °F) and winds that were estimated at 1,005 km/h (624 mph).

Casualty estimates for immediate deaths range from 40,000 to 75,000.[118][119][120] Total deaths by the end of 1945 may have reached 80,000.[1] Unlike Hiroshima's military death toll, only 150 soldiers were killed instantly, including thirty-six from the IJA 134th AAA Regiment of the 4th AAA Division.[69][121] At least eight known POWs died from the bombing and as many as 13 POWs may have died, including a British Commonwealth citizen,[122] and seven Dutch POWs.[123] One American POW, Joe Kieyoomia, was in Nagasaki at the time of the bombing but survived, reportedly having been shielded from the effects of the bomb by the concrete walls of his cell.[124] The radius of total destruction was about 1 mi (1.6 km), followed by fires across the northern portion of the city to 2 mi (3.2 km) south of the bomb.[125][126] About 58% of the Mitsubishi Arms Plant was damaged, and about 78% of the Mitsubishi Steel Works. The Mitsubishi Electric Works only suffered 10% structural damage as it was on the border of the main destruction zone.[127] The Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works, the factory that manufactured the type 91 torpedoes released in the attack on Pearl Harbor, was destroyed in the blast.[128] There is also a peace monument and Bell of Nagasaki in the Kokura.[129]

| Bombing of Nagasaki | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

Plans for more atomic attacks on Japan

Groves expected to have another atomic bomb ready for use on 19 August, with three more in September and a further three in October.[130] On 10 August, he sent a memorandum to Marshall in which he wrote that "the next bomb . . should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17 or 18 August." On the same day, Marshall endorsed the memo with the comment, "It is not to be released over Japan without express authority from the President."[130]

There was already discussion in the War Department about conserving the bombs in production until Operation Downfall had begun. "The problem now [13 August] is whether or not, assuming the Japanese do not capitulate, to continue dropping them every time one is made and shipped out there or whether to hold them ... and then pour them all on in a reasonably short time. Not all in one day, but over a short period. And that also takes into consideration the target that we are after. In other words, should we not concentrate on targets that will be of the greatest assistance to an invasion rather than industry, morale, psychology, and the like? Nearer the tactical use rather than other use."[130]

Two more Fat Man assemblies were readied. The third core was scheduled to leave Kirtland Field for Tinian on 12 August,[131] and Tibbets was ordered by Major General Curtis LeMay to return to Utah to collect it.[132] Robert Bacher was packaging it in Los Alamos when he received word from Groves that the shipment was suspended.[133]

Surrender of Japan and subsequent occupation

Until 9 August, the war council had still insisted on its four conditions for surrender. On that day Hirohito ordered Kido to "quickly control the situation... because the Soviet Union has declared war against us." He then held an Imperial conference during which he authorized minister Tōgō to notify the Allies that Japan would accept their terms on one condition, that the declaration "does not compromise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign ruler."[134]

On 10 August, the Japanese government presented a letter of protest for the atomic bombings to the government of the United States via the government of Switzerland.[135] On 12 August the Emperor informed the imperial family of his decision to surrender. One of his uncles, Prince Asaka, then asked whether the war would be continued if the kokutai could not be preserved. Hirohito simply replied "Of course."[136] As the Allied terms seemed to leave intact the principle of the preservation of the Throne, Hirohito recorded on 14 August his capitulation announcement which was broadcast to the Japanese nation the next day despite a short rebellion by militarists opposed to the surrender.

In his declaration, Hirohito referred to the atomic bombings:

Moreover, the enemy now possesses a new and terrible weapon with the power to destroy many innocent lives and do incalculable damage. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization. Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects, or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.

In his "Rescript to the soldiers and sailors" delivered on 17 August, he stressed the impact of the Soviet invasion and his decision to surrender, omitting any mention of the bombs.

During the year after the bombing, approximately 40,000 U.S. troops occupied Hiroshima while Nagasaki was occupied by 27,000 troops.

Depiction, public response and censorship

During the war "annihilationist and exterminationalist rhetoric" was tolerated at all levels of U.S. society; according to the UK embassy in Washington the Americans regarded the Japanese as "a nameless mass of vermin".[137] Caricatures depicting Japanese as less than human, e.g. monkeys, were common.[137] A 1944 opinion poll that asked what should be done with Japan found that 13% of the U.S. public were in favor of "killing off" all Japanese: men, women, and children.[138][139]

After the destruction of Hiroshima, Robert Oppenheimer felt "jubilant". He was seen "clasping his hands together like a prize-winning boxer". [140][141][142]

News of the atomic bombing was greeted enthusiastically in the U.S.; a poll in Fortune magazine in late 1945 showed a significant minority of Americans (22.7%) wishing that more atomic bombs could have been dropped on Japan.[143][144] The initial positive response was supported by the imagery presented to the public (mainly the powerful images of the mushroom cloud) and the censorship of photographs that showed corpses of people incinerated by the blast as well as photos of maimed survivors.[143] Wilfred Burchett was the first journalist to visit Hiroshima after the atom bomb was dropped, arriving alone by train from Tokyo on 2 September, the day of the formal surrender aboard the USS Missouri. His Morse code dispatch was printed by the Daily Express newspaper in London on 5 September 1945, entitled "The Atomic Plague", the first public report to mention the effects of radiation and nuclear fallout. His report is more fully recorded in his book, Shadow of Hiroshima.[145]

Burchett's reporting was unpopular with the U.S. military. The U.S. censors suppressed a supporting story submitted by George Weller of the Chicago Daily News, and accused Burchett of being under the sway of Japanese propaganda. William L. Laurence of The New York Times dismissed the reports on radiation sickness as Japanese efforts to undermine American morale, ignoring his own account of Hiroshima's radiation sickness published one week earlier.[146] During the U.S. occupation of Japan, and under General MacArthur's orders, Burchett was for a time barred entrance to Japan.[147] A member of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, Lieutenant Daniel McGovern, used a film crew to document the results. The film crew's work resulted in a three-hour documentary entitled The Effects of the Atomic Bombs Against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The documentary included images from hospitals showing the human effects of the bomb; it showed burned out buildings and cars, and rows of skulls and bones on the ground. When sent to the U.S., it was mentioned widely in the U.S. press, then quietly suppressed and never shown. It was classified "top secret" for the next 22 years.[148] During this time in America, it was a common practice for editors to keep graphic images of death out of films, magazines, and newspapers.[149][150] The total of 90,000 ft (27,000 m) of film shot by Lieutenant Daniel McGovern's cameramen had not been fully aired as of 2009. However, according to Greg Mitchell, with the 2004 documentary film Original Child Bomb, a small part of that footage managed to reach part of the American public "in the unflinching and powerful form its creators intended".[151]

Imagery of the atomic bombings was suppressed in Japan during the occupation[152] although some Japanese magazines had managed to publish images before the Allied occupation troops took control. The Allied occupation forces enforced censorship on anything "that might, directly or by inference, disturb public tranquility", and pictures of the effects on people on the ground were deemed inflammatory. A likely reason for the banning was that the images depicting burn victims and funeral pyres were similar to the widely circulated images taken in liberated Nazi concentration camps.[153]

Motion picture company Nippon Eigasha started sending cameramen to Nagasaki and Hiroshima in September 1945. On 24 October 1945, a U.S. military policeman stopped a Nippon Eigasha cameraman from continuing to film in Nagasaki. All Nippon Eigasha's reels were then confiscated by the American authorities. These reels were in turn requested by the Japanese government, declassified, and saved from oblivion. Some black-and-white motion pictures were released and shown for the first time to Japanese and American audiences in the years from 1968 to 1970.[151]

The public release of film footage of the city post attack, and some of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission research, about the human effects of the attack, was restricted during the occupation of Japan, and much of this information was censored until the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951, restoring control to the Japanese.[154]

However, worldwide, only the most sensitive, and detailed weapons effects information was censored during this period. There was no censorship of the factually written Hibakusha/survivor recounts. For example, the book Hiroshima written by Pulitzer Prize winner John Hersey, which was originally published in article form in the popular magazine The New Yorker,[155] on 31 August 1946. This book is reported to have reached Tokyo, in English, at least by January 1947 and the translated version was released in Japan in 1949.[156] Despite the fact that the article was planned to be published over four issues, "Hiroshima" made up the entire contents of one issue of the magazine.[157][158] The book narrates the stories of the lives of six bomb survivors from immediately prior, to months after, the dropping of the Little Boy bomb.[155][159]

Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission

In the spring of 1948, the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) was established in accordance with a presidential directive from Harry S. Truman to the National Academy of Sciences–National Research Council to conduct investigations of the late effects of radiation among the survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Among the casualties were found many unintended victims, including Allied POWs,[160] Korean and Chinese laborers, students from Malaya on scholarships, and some 3,200 Japanese American citizens.[161]

One of the early studies conducted by the ABCC was on the outcome of pregnancies occurring in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in a control city, Kure located 18 mi (29 km) south from Hiroshima, in order to discern the conditions and outcomes related to radiation exposure. One author has claimed that the ABCC refused to provide medical treatment to the survivors for better research results.[162] In 1975, the Radiation Effects Research Foundation was created to assume the responsibilities of ABCC.[163]

Hibakusha

The survivors of the bombings are called hibakusha (被爆者), a Japanese word that literally translates to "explosion-affected people." As of 31 March 2013[update], 201,779 hibakusha were recognized by the Japanese government, most living in Japan.[164] The government of Japan recognizes about 1% of these as having illnesses caused by radiation.[165] The memorials in Hiroshima and Nagasaki contain lists of the names of the hibakusha who are known to have died since the bombings. Updated annually on the anniversaries of the bombings, as of August 2013[update] the memorials record the names of almost 450,000 deceased hibakusha; 286,818 in Hiroshima[166] and 162,083 in Nagasaki.[167]

Double survivors

People who suffered the effects of both bombings are known as nijū hibakusha in Japan. On 24 March 2009, the Japanese government officially recognized Tsutomu Yamaguchi (1916–2010) as a double hibakusha. He was confirmed to be 3 km (1.9 mi) from ground zero in Hiroshima on a business trip when Little Boy was detonated. He was seriously burnt on his left side and spent the night in Hiroshima. He arrived at his home city of Nagasaki on 8 August, the day before Fat Man was dropped, and he was exposed to residual radiation while searching for his relatives. He was the first officially recognised survivor of both bombings.[168] He died on 4 January 2010, at the age of 93, after a battle with stomach cancer.[169] The 2006 documentary Twice Survived: The Doubly Atomic Bombed of Hiroshima and Nagasaki documented 165 nijū hibakusha, and was screened at the United Nations.[170]

Korean survivors

During the war, Japan brought as many as 670,000 Korean conscripts to Japan to work as forced labor.[171] About 20,000 Koreans were killed in Hiroshima and another 2,000 died in Nagasaki. Perhaps one in seven of the Hiroshima victims was of Korean ancestry. A Korean prince of the Joseon Dynasty, Yi Wu, died from the Hiroshima bombing.[172] For many years, Koreans had a difficult time fighting for recognition as atomic bomb victims and were denied health benefits. However, most issues have been addressed in recent years through lawsuits.[173]

Debate over bombings

The atomic bomb was more than a weapon of terrible destruction; it was a psychological weapon.— Henry L. Stimson, 1947[174]

The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender and the US's ethical justification for them has been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades. J. Samuel Walker wrote in an April 2005 overview of recent historiography on the issue, "the controversy over the use of the bomb seems certain to continue." He wrote that "The fundamental issue that has divided scholars over a period of nearly four decades is whether the use of the bomb was necessary to achieve victory in the war in the Pacific on terms satisfactory to the United States."[175]

Supporters of the bombings generally assert that they caused the Japanese surrender, preventing massive casualties on both sides in the planned invasion of Japan. One figure of speech, "One hundred million [subjects of the Japanese Empire] will die for the Emperor and Nation,"[176] served as a unifying slogan. Although some Japanese were taken prisoner,[177] most fought until they were killed or committed suicide.[178] Nearly 99% of the 21,000 defenders of Iwo Jima were killed,[177] and the last Japanese soldiers did not surrender until November 1949.[179] Of the 117,000 Japanese troops defending Okinawa in April–June 1945, 94% were killed.[177] Supporters also point to an order given by the Japanese War Ministry on 1 August 1944, ordering the execution of Allied prisoners of war when the POW-camp was in the combat zone.[180] As War Minister, Korechika Anami was opposed to the surrender. Immediately after Hiroshima, he commented, "I am convinced that the Americans had only one bomb, after all."[181] Eventually, Anami's arguments were overcome when Emperor Hirohito directly requested an end to the war himself.[182]

Those who oppose the bombings, among them many US military leaders as well as ex-president Herbert Hoover, argue that it was simply an extension of the already fierce conventional bombing campaign.[183] This, together with the sea blockade and the collapse of Germany (with its implications regarding redeployment), would also have led to a Japanese surrender – so the atomic bombings were militarily unnecessary. On the contrary, according to Kyoko Iriye Selden, "The most influential text is Truman's 1955 Memoirs, which states that the atomic bomb probably saved half a million US lives— anticipated casualties in an Allied invasion of Japan planned for November. Stimson subsequently talked of saving one million US casualties, and Churchill of saving one million American and half that number of British lives."[184]

Scholars have pointed out various alternatives that could have ended the war just as quickly without an invasion, but these alternatives could have resulted in the deaths of many more Japanese.[185]

As the United States dropped its atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, 1.6 million Soviet troops launched a surprise attack on the Japanese forces occupying eastern Asia. "The Soviet entry into the war played a much greater role than the atomic bombs in inducing Japan to surrender because it dashed any hope that Japan could terminate the war through Moscow's mediation", said Japanese historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, whose recently published Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan is based on recently declassified Soviet archives as well as US and Japanese documents.[186]

Legal situation in Japan

The Tokyo District Court, while denying a case for damages against the Japanese government, stated: [187]

... (b) that the dropping of atomic bombs as an act of hostilities was illegal under the rules of positive international law (taking both treaty law and customary law into consideration) then in force ... (c) that the dropping of atomic bombs also constituted a wrongful act on the plane of municipal law, ascribable to the United States and its President, Mr. Harry S. Truman; ... The aerial bombardment with atomic bombs of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was an illegal act of hostilities according to the rules of international law. It must be regarded as indiscriminate aerial bombardment of undefended cities, even if it were directed at military objectives only, inasmuch as it resulted in damage comparable to that caused by indiscriminate bombardment.

Notes

- ^ a b c d "Frequently Asked Questions #1". Radiation Effects Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 September 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ a b Giangreco 2009, pp. 2–3, 49–51.

- ^ Williams 1960, pp. 211, 274.

- ^ Williams 1960, p. 307.

- ^ Williams 1960, p. 527.

- ^ Long 1963, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 125–130.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 45–48.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 121–124.

- ^ "The Final Months of the War With Japan. Part III (note 24)". Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ Carroll, James (2007). House of War: The Pentagon and the Disastrous Rise of American Power. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 48. ISBN 0-618-87201-9.

- ^ Drea 1992, pp. 202–225.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 340.

- ^ a b Giangreco 2009, p. 112.

- ^ "March 9, 1945: Burning the Heart Out of the Enemy". Wired. Condé Nast Digital. 9 March 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Laurence M. Vance (14 August 2009). "Bombings Worse than Nagasaki and Hiroshima". The Future of Freedom Foundation. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Joseph Coleman (10 March 2005). "1945 Tokyo Firebombing Left Legacy of Terror, Pain". CommonDreams.org. Associated Press. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ a b Sandler 2001, pp. 24–26.

- ^ a b AMERICA'S DECISION TO DROP THE ATOMIC BOMB ON JAPAN[dubious ]

- ^ Kerr 1991, p. 207.

- ^ Zaloga & Noon 2010, p. 54.

- ^ Zaloga & Noon 2010, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Roosevelt, Frankin D; Churchill, Winston (August 19, 1943). "Quebec Agreement". atomicarchive.com.

- ^ Edwards, Gordon. "Canada's Role in the Atomic Bomb Programs of the United States, Britain, France and India". Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 89.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 12.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 509–510.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 522.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 511–516.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 534–536.

- ^ a b "Factsheets: 509th Operational Group". Air Force Historical Studies Office. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ "Hiroshima 60 Years Later". Review Journal 6 August 2005. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- ^ a b c d "509th Timeline: Inception to Hiroshima". The Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ a b "Silverplate: the Aircraft of the Manhattan Project". Cybermodeler.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2006. Retrieved 29 July 2006.

- ^ Krauss & Krauss 2005, p. 1.

- ^ "Reflections From Above: An American pilot's perspective on the mission which dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki". University of Washington. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ^ Gordin, Michael D. (2007). Five days in August: how World War II became a nuclear war. Princeton University Press. pp. 71, 74. ISBN 0-691-12818-9.

- ^ Campbell 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Craven & Cate 1953, p. 706.

- ^ Campbell 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Christman 1998, p. 176.

- ^ "Minutes of 3rd Target Committee Meeting 28 May 1945" (PDF). National Archives. Archived from the original on 9 August 2006. Retrieved 9 August 2006.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 528–529.

- ^ a b c d "Atomic Bomb: Decision—Target Committee, 10–11 May 1945". Archived from the original on 8 August 2005. Retrieved 6 August 2005.

- ^ Reischauer 1986, p. 101.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 530.

- ^ "The Information War in the Pacific, 1945".

- ^ Frank, Richard John (1999). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. Penguin Books. p. 153. ISBN 0-14-100146-1.

- ^ a b McNelly, Theodore H. (2000). "The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb". In Jacob Neufeld. Pearl Harbor to V-J Day: World War II in the Pacific. Diane Publishing Co. p. 138. ISBN 1-4379-1286-9.

- ^ a b c Lifton, Robert Jay (1987). Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima. University of North Carolina Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-8078-4344-X.

- ^ Craven, Wesley F.; Cate, James L. (1983). The Pacific-Matterhorn to Nagasaki: June 1944 to August 1945. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Air Force History & Museums Program. p. 656. ISBN 0-912799-07-2.

- ^ "空襲予告ビラ、高山市民が保管 市内で展示". 岐阜新聞社. Retrieved 31 January 2013.(Japanese)

- ^ Bungei Shunjū Senshi Kenkyūkai (1981). The Day man lost: Hiroshima. Kodansha International. p. 215. ISBN 0-87011-471-9.

- ^ Bradley, F.J. (1999). No Strategic Targets Left. Turner Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 0-912799-07-2.

- ^ Miller, Richard Lee (1986). Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing. Two-Sixty Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-02-921620-6.

- ^ Frank 1999, pp. 233–234. The meaning of mokusatsu can fall anywhere in the range of "ignore" to "treat with contempt".

- ^ Bix 1996, p. 290.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 372.

- ^ Thomas & Morgan-Witts 1977, pp. 326, 356, 370.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 64–65, 163.

- ^ Goldstein, Dillon & Wenger 1995, p. 41.

- ^ Giangreco 2009, pp. 70, 163.

- ^ a b c Steven Zaloga (October 19, 2010). Defense of Japan 1945 (Fortress). Osprey Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 1-8460-3687-9.

- ^ a b Zaloga & Noon 2010, p. 59.

- ^ United States Strategic Bombing Survey (June 1946). "U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". nuclearfiles.org. Archived from the original on 2004-10-11. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Thomas & Morgan-Witts 1977, pp. 222–225.

- ^ Thomas & Morgan-Witts 1977, p. 38.

- ^ Bodden, Valerie (2007). The Bombing of Hiroshima & Nagasaki. The Creative Company. p. 20. ISBN 1-58341-545-9.

- ^ Preston, Diana (2005). Before The Fallout: From Marie Curie to Hiroshima. Bloomsbury. p. 262. ISBN 0-8027-1445-5.

- ^ Waley, Paul (2003). Japanese Capitals in Historical Perspective: Place, Power and Memory in Kyoto, Edo and Tokyo. Psychology Press. p. 330. ISBN 0-7007-1409-X.

- ^ Rotter, Andrew J. (2008). Hiroshima: The World's Bomb. Oxford University Press. p. 267. ISBN 0-19-280437-5.

- ^ "Timeline #2 - the 509th; The Hiroshima Mission". Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ "Timeline #2- the 509th; The Hiroshima Mission". The Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ Allen 1969, p. 2566.

- ^ "The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima, Aug 6, 1945". www.cfo.doe.gov. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ Enola Gay, ISBN 0-671-81499-0, page 309

- ^ "Section 8.0 The First Nuclear Weapons". Nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ^ "The Bomb-"Little Boy"". The Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ "RADIATION DOSE RECONSTRUCTION U.S. OCCUPATION FORCES IN HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI, JAPAN, 1945–1946 (DNA 5512F)" (PDF). Archived from the original on 24 June 2006. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ^ 2. Hiroshima. "U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 19, 1946. President's Secretary's File, Truman Papers.". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. p. 9. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ 2. Hiroshima. "U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 19, 1946. President's Secretary's File, Truman Papers.". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. p. 6. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ Effort and Results. "Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 19, 1946. President's Secretary's File, Truman Papers.". p. 37. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ 2. Hiroshima. "U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 19, 1946. President's Secretary's File, Truman Papers.". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. p. 7. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ "HIROSHIMA & NAGASAKI BOMBING Facts about the Atomic Bomb:". Hiroshimacommittee.org. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ^ "Americans Killed by Atomic Bomb to be Honored in Hiroshima". June 4, 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "The Atomic Bomb (6 and 9 August 1945)". Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Knebel & Bailey 1960, pp. 175–201

- ^ a b "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". The Manhattan Engineer District. June 29, 1946. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ "Fulton Sun Retrospective". Retrieved 8 July 2007.[dead link]

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions #2". Radiation Effects Research Foundation.

- ^ "Special Exhibit 3". Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Kato, Toru (June 4, 1999). "A Short-Sighted Parrot". Geocities.jp. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ^ ""Hiroshima - 1945 & 2007" by Lyle (Hiroshi) Saxon, Images Through Glass, Tokyo". D.biglobe.ne.jp. 1945-08-06. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ^ "Hiroshima: A Visual Record". JapanFocus. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ^ "Japan". Kombe-jarvis.com. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ^ "Testimony of Akiko Takakura". Archived from the original on 16 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ "unesco.org". Archived from the original on 29 August 2005. Retrieved 6 August 2005.

- ^ "Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima". Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum. 6 August 1945. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ Bix 1996, p. 512

- ^ Radio Report to the American People on the Potsdam Conference by President Harry S. Truman, Delivered from the White House at 10 p.m, August 9, 1945

- ^ 3. Nagasaki "U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 19, 1946. President's Secretary's File, Truman Papers.". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. p. 15. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ Johnston, Robert. "Nagasaki atomic bombing, 1945". Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Sherwin & 2003, pp. 233–23.

- ^ Campbell 2005, p. 114.

- ^ Campbell, The Silverplate Bombers, 32.

- ^ a b c "Timeline #3- the 509th; The Nagasaki Mission". The Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ "Spitzer Personal Diary Page 25 (CGP-ASPI-025)". The Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 295

- ^ "Stories from Riken" (PDF). Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Wainstock 1996, p. 92

- ^ "The Atomic Bomb". Pbs.org. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Sodei 1998, p. ix

- ^ Rezelman, David; F.G. Gosling and Terrence R. Fehner (2000). "The atomic bombing of Nagasaki". The Manhattan Project: An Interactive History. U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.[dead link]

- ^ "Nagasaki's Mayor Slams U.S. for Nuke Arsenal". Fox News. Associated Press. 9 August 2005. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ Gar Alperovitz (August 6, 1996). The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb. Vintage. p. 534. ISBN 0-6797-6285-X.

- ^ "Nagasaki memorial adds British POW as A-bomb victim". The Japan Times. 9 August 1945. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^ "Two Dutch POWs join Nagasaki bomb victim list". The Japan Times. 9 August 1945. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^ "How Effective Was Navajo Code? One Former Captive Knows", News from Indian Country, August 1997.

- ^ "Radiation Dose Reconstruction; U.S. Occupation Forces in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, 1945–1946 (DNA 5512F)" (PDF). Archived from the original on 24 June 2006. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ^ "Nagasaki marks tragic anniversary". People's Daily. 10 August 2005. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ Nagasaki "U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 19, 1946. President's Secretary's File, Truman Papers.". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. p. 19. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Cook, Haruko & Theadore (1992). Japan at War: An Oral History. New York: The New Press. ISBN 0-7322-5605-4.

- ^ "小倉にある平和記念碑と長崎の鐘". Blog.goo.ne.jp. 3 October 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ a b c "The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II, A Collection of Primary Sources". National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 162. George Washington University. 13 August 1945.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 396–397.

- ^ Terkel, Studs (1 November 2007). "Paul Tibbets Interview". Aviation Publishing Group. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ Nichols 1987, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Kido Koichi nikki, Tokyo, Daigaku Shuppankai, 1966, p.1223

- ^ The Atomic Bombing of Japan Bombing Hiroshima & Nagasaki[self-published source?]

- ^ Terasaki Hidenari, Shôwa tennô dokuhakuroku, 1991, p.129